25 January, 2014

Self-service starts with self-assisted service

There is an on-going debate about Channel Shift and Self-Service in relation to customer services in the public sector, especially in social housing. The pros state that it improves residents’ accessibility to service, at the same time as dramatically reducing the cost per transaction. The cons argue that it excludes residents and leads to far greater demand and an increase in mistakes.

From my perspective, both have valid points, but when faced with a challenge, the smart organisations find a way of dealing with it. Self-service by utilising multiple channels to interact with residents such as the text, the web or smartphone apps, offers substantial benefits to both the resident in terms of accessibility, speed of service, and to the housing organisation in terms of reduced cost of service. Surely the question should not be whether to deploy self-service over multiple channels, but how to make this work more effectively.

The answer lies in what I term multi-modal interaction and in essence this recognises that self-service initially needs to be assisted and that at different times or stages of an enquiry, a different way of communication may be needed.

Just Browsing, Now I Need Help

Think about the experience in a department store. If your only access was to ask the shop assistant to bring from the store something you may want, the whole experience would not be great. However, to the contrary, if you have browsed and then need help in finding the right size or colour, you expect an assistant to be easily accessible. This is multi-modal working, you serve yourself up to the point that you need assistance.

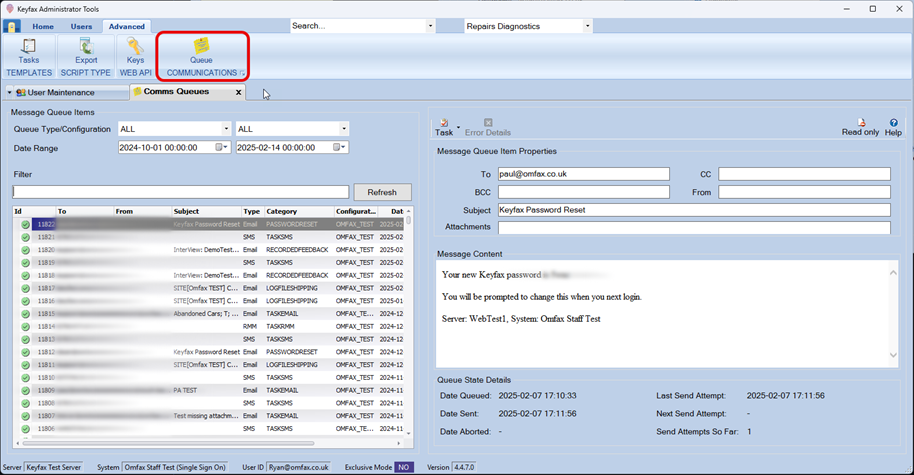

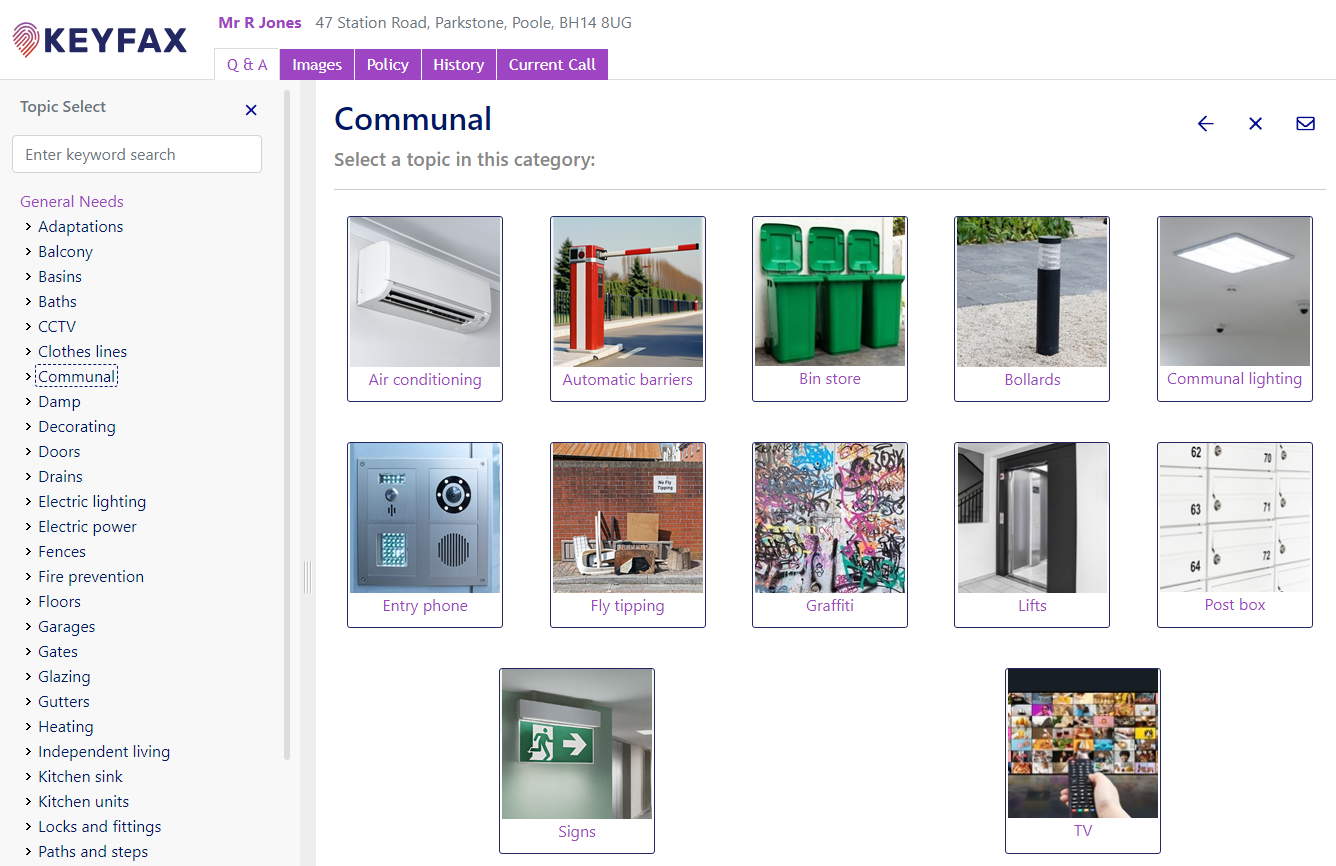

Technology exists to make this possible in everyday interactions that you have with your residents. For instance, they may start to register a service request online using a web-based form. However, if they find that the nature of their request is complex, they may want assistance, or if the request exceeds a particular threshold, you may want the process to be completed with operator assistance. This is where web-chat or resident call-back comes into play.

At a particular point in the transaction, the web-form turns into a live web-chat session. The advisor can guide the resident through a set of questions, complete information on the form that is visible to both the advisor and the resident and, if required, push information to the residents screen. You may even offer remote assistance to help guide them directly on their own computer or give them access to view yours; a highly visible, yet interactive experience.

If the enquiry gets to the point where web-chat is not quite sufficient to have a productive conversation, then immediately it can be superseded with a voice call, either utilising internet telephony, or through a call-back to the resident. The same joint browsing and information share can still be used.

I Would Serve Myself, If I Knew How

Most self-service deployments fail because they are initially too complex to use. You would never deploy a new internal system without first training your staff, however, we often expect that we can provide a

web-application for residents and expect them to intuitively use them like experts.

The multi-modal approach resolves this. Take a look at the way supermarkets are now introducing

self-service check-outs, sometimes these are far from reliable, nor intuitive. However, an assistant is on hand to help us to overcome our initial frustration and teach us how to use this service in the correct way. The result – we continue to use them.

I feel that housing organisations need to adopt a similar approach to self-service. If you place a service online and a resident is struggling to use it, there should be a way of them asking a question and getting immediate assistance. Investing the time in guiding the resident through the process will ensure that they make the transition to using self-service; an investment now that will generate substantial long-term payback.

There Is Never Just One Way Of Doing Something

I believe that to continually improve the quality and consistency of the service delivered, we have to think in terms of how the multiple ways we communicate with residents best work together. The wealth of possibilities that are now open to us in the way we interact with residents is most definitely a journey and not a destination; we just need to select the best route to take.